1.

I have a love/hate relationship with metafiction: love, because it’s an invigorating psychology experiment that presses the art and the mind to the point where it snaps and collapses in on itself—a gloriously postmodern head trip. It excites a young writer like hallucinogens; and to a mature writer, when it’s done well (as by Vonnegut, for example), it demonstrates the fluidity of authorship and deconstructs the form without destroying it, revealing the elegant architecture of literature that is the architecture, ultimately, of the self.

Hate because, like Starbucks and Andy Warhol, it is cloyingly vapid, a cheap trick hiding behind a veneer of artistic sophistication. It’s a self-consumptive obsession with authorship that eschews craft. Metafiction titillates the young male narcissist writer’s brain because it is masturbatory, suggesting that in order to be a writer one need only say the magic words: I am a writer; that one might write about oneself writing.

As a young man, I was undoubtedly caught in this same snare (if I am not still caught); the result of loving one’s cage—the choice to stay trapped—is the slow atrophy of one’s work, if not of the exercise itself: why bother to commit to writing that which is ultimately already enshrined in the experience of being a writer? One conceives of his looming and always nascent novel as a reflection of his life, and of his life (also tragically nascent) ultimately as a foregrounding of his novel; his character is his self and his self is his character, and thus neither gets written.

I remember being in someone’s apartment somewhere in the greater metropolitan Boston area in my first or second year of college, exquisitely wasted, standing in the bathroom and gazing at my own reflection in the mirror while I pissed, thinking: “Yes, yes, yes! This is inspiration! This is the moment the character will realize the truth! That he is nothing but a character, the very invention of his drunken, deranged creator, a horrible, debauched demiurge … one who is in fact himself! He is I and I am him, slim with the tilted brim! Oh the horror! Here, he will smash the mirror with his fist, hurl his bottle against the wall, and cry out to his creator, but no one will hear him! Oh, the genius of it all!” This is perhaps a soft exaggeration, but the general trend in my thinking should be clear: I had the fury but not the story. There would be no such climax because there was no foregrounding, no plot, no conflict beyond the pale and (though I suppose I can be excused for not having known this then) hackneyed confrontation of the self with his own meaninglessness, artlessly conceived of as a character’s blunt and material recognition of his own fictional nature. Soft putty. I went back to the living room and […], and the glorious vision of this alleged “novel” faded within the hour.

But the dream of the metafictional masterpiece never died. It rode through various of my completed works and partial experiments during college: I wrote a short story in which the narrator’s three possible futures play out in succession before his eyes; I wrote a poetic diatribe in which the poet’s own self-aggrandizement meets with ironic debasement within the confines of his own apartment and poem; sophomore year I started what was to be a novella called Who Exactly is James? in which the narrator and I attempt to dissect our relationship with our father and a girl named Jill Eastey through a series of self-conscious and evasive vignettes involving the college dormitory elevator, Cornish New Hampshire, car rides, and the JD Salinger myth, the sole link between them being a nagging awareness of its all being a literary facade for the author’s real life. The fact that the book never came to fruition demonstrates that these concerns were ultimately not artistic but personal, and that my small personal tragedies and anxieties were not sustainable meat for real writing.

2.

I had this vision of myself as a writer, like in the future, eerily indicative of my perceptions of the art form, the persona, and the myth: it’s dark in my chamber (which I pictured as an iteration of a college dorm room) and I am a hunched and key-pecking silhouette at the glow of my desktop IBM Aptiva screen. At my side is a tall glass—more specifically, the pint-sized azure plastic tumbler I counted as my sole cup in college. One is welcome to imagine it filled with a brown liquor, germane to the tortured-American-writer paradigm. I type, sigh in the darkness, sip. Someone enters, maybe after knocking and receiving no response. “Mr. Kersey?” they intone, probably a young woman or maybe an obsequious young man, eager to make my legendary acquaintance, very informed by Kevin Costner’s approach to James Earl Jones in the second act of Field of Dreams. I guess they are calling me “Mr. Kersey” because by the historical point of this particular vision I am old enough to be addressed thus by a college student (my demographic at the time of this vision—see, the vision doubles as a fantasy of my own approach to an esteemed writer or professor). The student maybe says it two or three times, punctuating with “um,” and “excuse me,” and “well …” That’s when I utter a single, whispery what …? And they either repeat “Mr. Kersey?” or they start to ask their question (something along the lines of, “I was wondering if we could talk …”) or just say, “umm …” again, but before any real exchange can take place I bellow “WHAT?!” and hurl my plastic tumbler laterally across the room where it smashes (now miraculously made of glass) against the wall and leaves a bloody, brown, legendary mark, and when I turn to howl at the intruder my face is revealed in the half-light: the glowing eyes and fangy mouth of an animal, a devil, a man driven mad by drink and literature (the same thing, really), and the kid dashes out and flees, face tear-streaked, from my townhouse or college dormitory or dark tower or whatever it is, all the while the music building and my voice either a howl of pain or a mad cackle of hysteria.

This vision says a lot about a lot of things, especially my failure to countenance the reality of craftsmanship at that age (note the irrelevance of my actual creative output in this fantasy). And it captures with pretty embarrassing clarity the truth about the myth of the author. As a child, my human identity and perception were transformed and to a certain extent created by books. I learned more about the human condition from books than from being alive, and eventually I recognized that literature was the true and good spiritual pursuit. Like many writers, I wanted from a young age to be a part of that cult and to obtain the advantages it entailed: the agency to convey my unique perspective (because we were all taught our perspectives were unique) to a wide network of readers; to just shout out into the void and have all these people throughout history hear me and think what I say is not only legitimate but important; and—inevitably, as puberty ran its peremptory course and all facets of the human condition were revealed as mere reflections of the sex drive—I figured I could get girls to like me if I became a writer because look: words (I thought I had discovered, as no one had yet explained that there were whole theories to this and that whole careers had been built on it) are just symbols, and at this erupent age I could believe that behind all those symbols there’s maybe only one thing looming in the platonic background and it’s sex sex sex, that purest reason, echoing even in the most stolid prose like the big bang radio waves that color our very universe: sex as prime objective, subsumptive of everything, and categorically outside the reach of a twelve-year-old nerdling with a stack of sci-fi under his arm. The whole writer’s legacy thing is the same as the urge to procreate. Make a piece of you live forever. It’s just that somewhere along the timeline of Western comfort and sophistication, we started seeing the evolutionary imperative in a more abstract, symbolic sort of way (as humans are wont to do). Now here we are with five-thousand undergraduate writing programs and a trade paperback industry, and people go on writers’ retreats more to get laid than to write.

3.

In 2001, I was included in a printed poetry collection full of authors I knew. We had pooled our money and self-published the book. When constructing my author bio for the anthology, I wrote “I enjoy meta-ness and narrative,” clinging not only to my precious prefix but also to a first-person construction. I’m pretty sure the latter was deliberate, conceived as a stubbornly humble self-bio, surrounded as it was by a cluster of third-person bios that were written, I knew very well, by the authors themselves, which I found—and still find—pretentious in the highest, if appropriately conventional. In the first printing of this collection, the Author Bio section was located at the beginning of the book. It prefixed even the table of contents, which is pretty indicative of where our priorities were. Thank God we had the aesthetic sense to take this entire ridiculous segment out of subsequent printings.

We (me and the writers I knew) were listening to a lot of Anticon in those days. I was rapt by Dose One—still am, if the mood strikes me, and I go back and listen to those few millennial albums where he seemed like a pinhole of freshness emerging on a torpid scene. Circle was marvelously meta-, and he seemed to struggle with the same love/hate relationship with the form as I did, plowing through miraculous bars of abstract poetry while occasionally deflating into self-exhausted lines like “I should definitely count to twenty now: 1, 2,” etc, or “blah blah blah.” But of all the lines regarding the snare of metafictional self-aggrandizement, the most lucid comes from the first cLOUDDEAD compilation: “Do you know how many times I’ve thought about writing about the paper I’m writing on?”

I took a fiction workshop with Rick Reiken, who had us re-read The Things They Carried, a monolith in the metafictional form, and who demonstrated, by means of three concentric circles, the relationship between author, narrator, and character (The Three Tims Theorem … my title, not Reiken’s). I read the indelible David Foster Wallace, who is always being propped up as the postmodern icon but who by and large didn’t really dawdle in overt metafiction (though the argument can easily be made that all his work—all literature, really—is inherently metafictional in the sense that a dynamic boundary exists and is always to a greater or lesser extent transgressed between the author, narrator, and character). An influential professor introduced me to Witold Gombrowicz’s Cosmos, and I studied Kafka’s The Castle, forerunners of the self-consciousness of late postmodern pop metafictionistas.

And then near the end of college I read a popular novel that had been lauded for its experimental use of metafiction. And there did my love affair with metafiction cusp and descend into disillusionment and a disgust I would eventually channel inward. The book felt like a nadir of craftsmanship, and for the first time I saw as with un-bandaged eyes the trick, the long-con that is metafiction done shoddily: how every scene, theme, and character, even the precious boy hero whom the reader is supposed to adore, fundamentally collapses into the author in a deluge of selfishness and narcissism; the way every break of the fourth wall reveals a weakness, a chink in the craft of literary fiction—chinks which the author didn’t bother to repair or even cover up but chose rather to exploit for the purpose of being cute, clever, and cynical. Oh, the meta-ness (read: horror) of it all; the cult of me, me, me! I read it—struggled through it, really, after casting it down in anger several times—and came out with a whole new sense of self-revulsion. Metafiction, my yen, my idol … a worthless bauble. I felt tricked, deluded by an ancient evil while being distracted by a shiny object. Albeit, the trick was working on the public. Everyone loved the book. Just as the flavor of beer is subdued, even by European exporters, to appeal to the simplistic palates of the American consumer, so has the most banal and shameless mediocrity of craft proven to be the winning recipe for literary experimentation in the marketplace.

Never again could I be bamboozled into buying into metafiction at face value; although for me, as for all writers of our time (all time?), the infatuation was terminal. What remained was to understand the true nature of the condition—to learn to see beyond the affectation and write from the heart of the form.

4.

In the case of the aforementioned metafictional novel, the market (and critical public opinion) was responding to a trick. In this particular case the trick was uniquely bald, and so the pattern was evident: give us something kind of weird to think about and we’ll laud you (though we might not actually think about what you gave us to think about). Metafiction is no better understood now than it was in the 60s, despite the fact that everyone is looking at it, constantly, saying either “Wow!” or “Ugh!” (if they’re saying anything at all, if it’s not totally indistinguishable from regular fiction these days).

Metafiction’s power is not in its novelty but in its demonstration of the naiveté of realism in art, the revelation that all fiction is fundamentally metafiction, or at least has a responsibility to be self-aware of the illusion of verisimilitude. Once one grasps this (and it’s not hard to grasp if one is willing to stop laughing at the irony for a minute), there’s a whole new dilemma: if fiction is fake, and if we’ve been worrying that academic bone for a century (at least), then why write fiction at all?

As an adult, I went back to David Foster Wallace. And I realized that Wallace is not so much a storyteller as he is a philosopher whose medium happens to be creative writing. His fiction is a demonstration of his ideas; one recurrent thesis of his is that postmodernism—especially its metafictional sensibility—is passé when treated as some miraculous discovery, or if glared at with resentful, ironical eyes. The postmodern world—the reflections thereof, the reinventions thereof—has to be made a bastion for a sincerity, a love of the audience so ferocious it makes us “more fucking human,” and this means that even its most profound discovery, the subjectivity of perception, the awareness of narrative conceit, the whole play-within-a-play, self-aware-character, breaking-the-fourth-wall thing … it has to be, in Wallace’s model of love, at the service of a wider motive than mere self-reference. The lampooning of craft through metafiction—the self-righteous disdain for artifice (ahem: art)—amounts to a bratty resentment of fiction’s ultimate naiveté: a hatred of the form. This so often perverts into spite for the audience (for their gullibility) and self-hatred (for the author’s pretension and impotence), both of which are poisonous counterfeits to love. So we have to build a heaven in hell’s despite, here in the world of metafiction, metalife, etc. This is the thesis of Wallace’s “Westward the Course of Empire …” and it is a recurring idea in most of his fiction.

The thing that is vexing about this, from a writer’s perspective, is that his whole philosophical code presupposes metafiction as an unavoidable reality in contemporary literature. It’s as though he’s demonstrated—in the manner of Joyce and Barth before him, or of Picasso or Pollock or Warhol—an irrefutable aspect of modern and postmodernist art. Can one still write a story without the meta-story, a tale in the old school of plain old fictive narration? Can one write a plot that is not inherently a demonstration of a philosophical point? Or is regular imaginative fiction truly passé, half-assed, constituting either a conservative reaction or an artistic retreat? Is the intellectual world over that, and am I a relevant writer if I never push that particular envelop in whatever direction it is being pushed, like the real relevant artists of our time and times past?

5.

I’ve never had a lot of luck with submissions. Most of the fiction I have placed is, in some way or another, theoretically grounded in a self-awareness of form: the characters have an inkling of the absurdity of their situation, a crisis of perspective, or the narrative structure itself evokes a familiar pattern with appropriate irony; whereas my more pure stories—the single-level tales about humans with material or emotional problems, rather than ontological conundrums—languish in slush piles and eventually generate boilerplate rejections. Does this speak to the fact that the so-called market or the intellectual zeitgeist (ahem: the cadre of grad-school internet-lit editors) is, as I’ve suggested, actually over fiction that lacks the philosophical underpinnings of metafictional postmodernism? Or does it mean that I have mastered, like everyone else, the ironic exercise in meta-storytelling, while my skills as a craftsman of actual fiction—as a writer—are underdeveloped? And what brought about this miseducation?

As any good post-Marxists, I’m going to go ahead and suggest that late-stage capitalism is to blame—at least a theoretical literary analog to the economic model. It’s not metafiction that’s driving the zeitgeist: it’s gimmickry. It’s the illusion of innovation. Traditional tales stand up to hard criticism, but books with multicolored ink or with pages that have holes cut in them, those will sell regardless of content. And it’s the internet, with its acceleration of commercialism, its promise of viral popularity, its capital of views and hits. Savvy content-providers can’t afford to waste time with slow fiction, with stuff that is erudite or subtle or boring. The easy wow gets the view; and sure, maybe no one, like, actually reads the story all the way through—who could, with all the ad banners and hyperlinks?—but this is a game about likes and retweets, not about content. The writer as phenomenon is what matters. The traditional author bio is neither subordinate nor dominant to the literary content produced by the living person; instead, the content and the bio both serve as parts of an avatarial package product: the internet self as content, with its constellation of associations and permutations (not only literary output but posts, updates, facebook and twitter handles, pinterests, images, personal blogs, paypal buttons, etc.), all of which is inherently postmodern and, from a literary perspective, a supreme (and supremely transparent) act of metafiction.

It isn’t metafiction that’s to blame: it’s good old-fashioned narcissism. Art is an act of communion, and a selfish artist is no less a monster than a selfish talker, a selfish teacher, or a selfish lover. It’s a vacuum in the heart of our culture that renders all earnest form of expression valueless, all audiences cynical. The only antidote to this vacuity, for a writer, is craftsmanship. We must be students of the form. We must forget ourselves and fall in love with literature again. We must re-read everything; when we do, we’ll realize that Shakespeare was doing postmodernism four-hundred years ago. We are not doing anything new with metafiction or with our lives, most likely. We are all doing the same thing: writing. It is an action, like eating and sleeping and having sex, that cannot only be talked about or imitated. It must be pursued shamelessly, with naked sincerity. If not, we will die—fiction will die—and there will be no stories, just a stain on a wall where a frustrated drinker (who should have been writing) smashed his glass.

________________________________

Summer, 2014

The Title is drawn from James Tate’s “On Teaching the Ape to Write Poems”

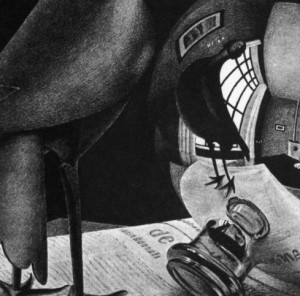

Image: detail from MC Escher’s Still Life with Spherical Mirror. All M.C. Escher works © 2014 The M.C. Escher Company – the Netherlands. All rights reserved. Used by permission. www.mcescher.com