“We go in the mental frame of adventure, aggressiveness, zeal. Thus does fear vanish and the ghosts become creatures of mind-weft; thus does our elan burst the under-earth terror.”

—Guyal of Sfere, from Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth

1. Tohu Wa-Bohu

I didn’t think I’d be able to write this essay about Dungeons & Dragons because there is nothing to compare it to. The text—the D&D universe, which is a multiverse, a multi-player, multi-access cooperative psychodrama with no beginning or end—is not comparable to the world because it is the same thing as the world. Its terrain is that of Tolkien, of Snorri Sturluson, of the anonymous writer of the Book of J. All of our languages and sciences and political events, those real and those imagined, are part of the same mess of myth.

So I can tell you that I played an hour here or two hours there, or read this or that book, or designed this or that campaign—but I can’t tell you that after that, I went out into the real world and found remarkable parallels. Because it was all the same dream. The most I can tell you is that I enjoyed playing it out.

I decided to learn how to play Dungeons & Dragons because of a conversation I had with five students in the library. This was a research class, and the topic had arisen from a context of postmodern pop-culture referents—memes we recognize but do not fully understand. Several of them had seen the children of Stranger Things playing the iconic fantasy role-playing game, but none of them knew much about it. They asked how it was played, and I told them that I didn’t really know either—but I told them what little I knew, and when they said it sounded as though I did know how it was played, I said, “I’m pretty sure it’s a lot more complicated than that.” And when they said, “We should play,” I huffed and rolled my eyes so as to put them off the notion.

Because to me it always seemed like a steep-ass learning curve—one I was always just a little too busy or lazy to begin climbing. But in retrospect, it feels as though I’ve spent my whole life preparing to play Dungeons & Dragons. I regularly use the game’s name as a metaphor for any sort of complex, strategical nerdiness, fantasy or otherwise. And as an adolescent I fooled with Nintendo RPGs and read a lot of fantasy fiction. But the shadow of the monolith itself always loomed in the distance, intimidating and arcane.

Chance had brought me to this crisis: literally a moment of choice.

So I said okay, I’d learn. But it would take me a while—maybe months—to prepare to DM. They said, “What’s DM?” and I said, “Give me until after winter break.”

2. Whence this Dungeon Master

Many times in my teaching career I have taught Sam Lipsyte’s “The Dungeon Master”—It’s a period piece, like Stranger Things, a cheeky contemporary meditation on male puberty and the cruelties of a sadistic DM. But at the tale’s heart are the sacred limitations of the mind realm. “Stay the fuck out of my mind realm,” the DM warns his father. Our sidelined narrator watches the DM destroy his players’ jouissance with one fruitless, tasteless campaign after another, but self-actualization in the real world, tragic or no, proves ultimately unavoidable. It’s a sharp story, and I think I love it in part because it arose from the same cultural milieu as I did. An awareness of the rudiments of D&D was, as far as I can tell, an involuntary part of being a literate American boy in the eighties.

By the time I was born, the franchise was almost a decade old. There had already been a popularity blip, a conservative backlash, a re-integration narrative. My friend’s mother spoke of the work of Satan in a stern voice. Metallica spoke of “Ktulu.” Hollywood mini-fortunes were spent to produce films like Dragonslayer and Willow. The Legend of Zelda was mass-produced in gold-plated cartridges. One had to abstain from media not to understand the basic laws of fantasy: heroes kill monsters with steel or with magic, and they get treasure and prestige.

I read CS Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia as a child, and The Lord of the Rings changed my adolescent life. And I upheld the ideal of the unspoiled chain of authorship. The esteem of these auteurs and the purity of their visions comforted me. In their person was ultimate authority; there could be no contradiction. I was a high fantasy fundamentalist.

By the time I’d finished Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, I was after another world with a comparable complexity. I considered reading the Dragonlance Chronicles, but there was something about them that irritated a nerve of early cynicism in me. Literary commodification spooked me. I already suspected Danielle Steele and possibly even Stephen King of being in essence a name brand front for a team of hacks who cranked out dross narratives for the market at the expense of authenticity (a paranoia that takes the recurring form, in adult academia, of anxiety over Shakespearean authorship), and these books—all published by TSR, Inc.—were brazen, shameless examples of pop merch fantasy.

What I did not understand then (because I did not play the game) was that unlike Tolkien’s Middle Earth or Robert Jordan’s Westlands, this world—the D&D multiverse as it has come to be known—was inherently co-authored.

And it was inherently commercial.

Okay, maybe not inherently. Maybe it was incidental that fantasy roll-playing games found cultural representation in commercial products: the red box starter set, or the miniatures, or the hundreds of modules and video games and books. Maybe it says more about our country’s economic model than anything else: that myth, like everything relevant, is rendered as a commodity.

But you can’t own Dungeons & Dragons, really. Not like one man can own his novels and characters. Middle Earth belongs to Tolkien. You can’t rip it out of the fabric of his biography without damaging it. But D&D is open-source. Wizards of the Coasts owns the commercial licensing rights; but you don’t need permission to play it, and no one can stop you from playing it wrong.

3. The Smithy of my Soul

I played it wrong. I didn’t have the sort of time I might’ve had if I’d learned this stuff when I was fifteen, but I knew the momentum would let up if I didn’t get ready by Christmas.

As the ostensible point of the project was to play D&D as seen on Netflix’s Stranger Things, I bought a copy of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide and started reading. The show takes place in ’83, so they probably would have been playing this version (which I would soon learn was the second of more than six editions).

I knew that many D&D campaigns are played on grid paper, and then a colleague of mine told me about hex paper, and so with no regard for dimension I made my own hex grid on one of my daughter’s giant drawing sheets with a ruler and a sharpie marker. I marked each hex with a number and recorded some stats so that when my players went there, I’d know what to tell them was going on. But there were forty-something hexes, so I skimped on some, and at first I wrote fruits/nuts for some hexes before ultimately deciding that it was too much of a hassle, in my novice state, to worry about food.

I didn’t know what to take seriously and what to ignore. The book seemed to presume I knew more than I did (I hadn’t considered starting with the Player’s Handbook). So I took what I could for tips and I ignored what was too complicated.

Egregiously, I ignored—or, better said: read, forgot, and then bluffed—rules on weapons, proficiencies, and damage. Same with the rules regarding short distances and proximities: who is where in a melee, and how many feet each character can move per turn, and the reach distance of a monster or a character. And, predictably, we forwent miniatures of any merit—just threw a handful of cap erasers down on the page with its blank hexes and called them the adventure party.

Maybe I could have waited. Maybe I could have done better homework. Maybe I could have mastered the charts and the math and then mounted a proper campaign by the books. But maybe I couldn’t have. Maybe you never understand the mechanics of gameplay until you play. And as a teacher—one who has learned never to plan further than a week ahead—I knew this was probably the case.

So we played. Three male students, two female students, and a grown-ass man, an English teacher, as their DM.

4. Day One: Character Creation

The first day of the unofficial and highly experimental D&D session, we made characters. We used Method I from the guidebook, rolling four d6s (six-sided dice) and discarding each low die, and slotting abilities according to preference. I was the one who knew the most, and I knew very little. I tried to explain races and classes, also according to the first edition, and I illustrated alignment on the whiteboard, but I had to admit that I didn’t know how any of this factored into gameplay. I didn’t understand proficiencies or skills yet, nor did I understand magic. Two students chose to play as magic-users, and I had to tell them they’d have to wait until I figured out what that meant to award them any modicum of magical ability beyond the single heal or hurt spell-per-day I’d arbitrarily given them.

What I should have told them, I realize now, is: get a handbook and figure your character out. I misunderstood, at that time, the role of the Dungeon Master. I was still thinking like a teacher thinks in his first or second year: I was flustered by questions, and lacunae terrified me. I’d yet to learn that in D&D, as in all pursuits in the mind realm, the student is the master.

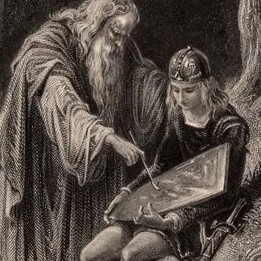

Since we’d only scheduled time to play for forty-minute blasts, once the characters were drafted we were done for the day. And I, grim journeyman dungeon master, returned to my study to pore over my ancient codices and forbidden incunabula, searching for the keys to this multiverse.

5. Sword and Sorcery, Inc.

Dungeons & Dragons is just one—perhaps the most robust—shoot of the Sword and Sorcery family tree, itself a sub-species of the Fantasy genre. The term “Sword and Sorcery,” coined in the sixties and often distinguished from Epic or High Fantasy, cannot and should not be regarded as restrictive or even denotative. But the term does have an assuring concreteness. There is combat and magic. Setting and conflict serve to foil and shape characters, who are defined by their martial or magical practice.

Sword and Sorcery’s lineage is as old as mythology—let’s just go ahead and call the oldest human narratives of all time essentially fantasy tales of might and magic—and its American antecedents span the dial, from the hysterical romantic Poe to the naked realist Jack London, whose pit-fight experiments with setting and character are essentially Sword and Sorcery stories for dogs.

But the immediate family—what might be termed Modern Sword and Sorcery—stems from the influence of a black trinity of depression era writers whose work all appeared, at intervals, in the notorious Weird Tales periodical. These are: Clark Ashton Smith (whose vast and macabre imagination found expression in prose, poetry, and visual art); Robert E. Howard (who wrote more than a hundred stories, including the original Conan the Barbarian tales, before ending his life at an obscene thirty); and big daddy HP Lovecraft (of Cthulhu fame). These guys put in the trenchwork of crafting an aesthetic akin to but separate from the epic model, as typified by Tolkien (that other obvious master influence): theirs is a fatal realm, an often bleak and occasionally repulsive milieu for baroque carnage and sinister magic. Sword and Sorcery is lapsarian. Its world is rotting on the vine of imagination.

Jack Vance’s 1950 landmark collection of Sword and Sorcery tales is aptly called The Dying Earth. In its six stories, magi and rogues compete for power and secret knowledge in a realm of dreams and nightmares we are made to understand is a nearly-extinct planet earth. The dying earth’s variety and imagery are astounding, from the genetic twists of flora to the grotesque tools and deliriously-titled spells of the magicians. Here, amoral and Faustian wizards live lives of hermetic grandiosity amid complicated old ruins, wielding awesome powers in spite of barbarian nature; but their powers are checked by two weird strictures: they can only remember a certain number of spells at one time, and they lose all memory of the incantation once it’s cast, requiring re-study.

To a fresh eye—one that opened in the eighties, and has lived his entire life in a post-D&D America—it feels curiously prodigious that Vance should so casually invent such a code for his characters. He seems to be anticipating gameplay.

In reality, gameplay is invoking him. Gary Gygax—the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons—has called Vance “the very best of all the authors of imaginative fiction” and even recommended the dying world as a setting for D&D campaigns.

Because of the impact of Vance’s work on early D&D designers, the laws that govern Vance’s sorcerers have come to govern magic-user characters. The original rules state that “a Magic-User can use a given spell but once during any given day”; the advanced edition of the Player’s Handbook states that “each character able to cast spells can remember only a certain number at any given level”; and by the time the fifth edition comes around—more than half a century after The Dying Earth’s initial publication—the notion of so-called Vancian spellcasting is entrenched as code in the form of “spell slots.” This is one of the most cogent examples of the game’s debt to the world of fiction.

Look: as an English teacher, I approach this whole thing from an angle of admitted logocentricism. I felt I couldn’t understand the game without reading a chunky sample of its sources—including those volumes I’d been so pompous to snub in my youth. The first Dragonlance book and first few Forgotten Realms books are radiant acts of pop high fantasy. Absorption is easy because we know the races of the fantasy multiverse already, as well as the well-trod allegory of the sacred object that must be delivered (hail, again, Mr. Tolkien!). Action and imagery supersede verisimilitude, and there is no subtlety, but in general the stories are strong on character, strong on plot, and strong on tips and campaign fuel for the budding DM.

And by this point in the Sword and Sorcery tradition, the crossbreeding of fantasy world-shaping and canonical gameplay is heavy-handed, as exemplified by Dragons of Autumn Twilight (a TSR publication, written by TSR employees and explicitly tied to many D&D modules). In an early combat encounter, we find Raistlin, a very kick-ass and scary character, “lost in the concentration necessary to a magic-user casting a spell,” and we are warned that “disturbing him now might have drastic consequences, causing the mage to forget the spell or worse—to miscast the spell.” In a flare of poetry, we learn that “the words of magic flame in the mind, then flicker and die when the spell is cast,” but Hickman and Weis append the didactic injunction that “each spell burns up some of the magician’s physical and mental energy until he is totally exhausted and must rest before he can use his magic again”—practically instruction manual material.

Conversely, the instruction manuals are compelling reads. The introduction to the fifth edition—“Worlds of Adventure”—is some of the most inspiring Sword and Sorcery prose I’ve encountered this year. At its heart is a sense that we have entered a boundless (if bleak, if bloody) world—a mind realm. The call to adventure is the true and sole criterion for the genre. The rest builds itself on demand.

6. Day Two: Call to Adventure

During our second after-school sesh, the adventurers entered the forest. They’d banded up the previous night in a village inn on the southern fringe of a treacherous old-growth valley. Still having never read any actual player’s manual at this point, I’d equipped them with no armor and plain wooden clubs—essentially sticks, to which I’d randomly assigned a d4 attack (with no modifiers—I still knew nothing of proficiency or ability bonuses).

And they were made to fight wolves and one brown bear, and when they found a woodsman’s hut, they tried to break in, but failed, and then the woodsman showed up and Vincenza (elven magic-user with a high charisma score—purely coincidental, as I still didn’t know how to apply bonuses) persuaded him on an 80-percent die roll to let them in and let them sleep and heal. He told them about the fire to the north, and of the river of lava that flowed along the eastern edge of the valley, and he told them they should go home, return to the village inn. Ahead lay certain death for greenhorns like them. But of course they pressed on, doom-bound, into the as-of-yet unimagined forest.

Forty minutes were up. We were done for the day.

7. What Biron Said

That weekend I spoke to Biron, who is forty-five, about the students and the sessions and the books I’d been reading—this portal I’d spied in my childhood that I was only now opening. He told me two things.

First: that it was obvious the underground has become mainstream. These were not deep fantasy nerds I was playing with; most of them were not even fantasy novel readers. He said that this show I was talking about—Stranger Things, a Netflix original series—had boosted D&D’s profile in a calculated and cynical bid, as part of a marketing aesthetic. They were playing the nostalgia card—selling D&D in a time of Star Wars reboots and Ghostbusters reboots and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles reboots. And I was buying.

And second: that he knows a guy who DMs. Has a bunch of people over to his house every couple weeks. Adult gamers. They do all the regular stuff adults do, like drink and smoke and curse and gossip, but they do it while role-playing. It was an old set, he said—been playing together for years. Got a whole world in there. Several worlds. Multiple different games: D&D, Pathfinder, Warhammer, Call of Cthulhu …

And war games. All kinds of war games. Axis and Allies, Conquest of Empire, Shogun … those dudes play more war games these days than anything else. He said he went over and hung out one time. Tried to play it, but either it was too complicated or they played it too fast for him. They were rolling and calculating scores before Biron knew what they were responding to. He mostly sat back and watched as one by one, his tiny ships and carriers and airplanes were removed from the board or appropriated by other players until all he had was his beer and his seat and a satellite view of the world’s oceans in the throes of a carnage so tiny he’d never see any bloodshed. There were wee families, he told me, stranded somewhere in the mind realm, deprived of their husbands and fathers, and the only evidence were these scattered plastic-cast war toys.

8. It’s a Small War After All

The whole miniature thing can seem, to a newb at least, kind of irrelevant. Like: if this is all imaginary, do we want to limit ourselves to the range of movement offered by toys? Do we need to?

But that’s the kind of newb thinking that doesn’t take into account the complexities of combat: distance, angle, approach. Dimensional teamwork. Combat specificity. The level of detail that always distinguishes strong fantasy from gross parody.

One time I wandered into a hobby shop. Inside, dozens of people were playing several games, none of which I understood. And on one board stood a rampant dragon, wings flared, fully painted. It could hardly be called a miniature. It was a gorgeous piece. Around it on the blue and green tiled board stood a dozen other miniatures: humanoid figures, a beast or two, and one cylindrical structure, either a castle or a siege tower. And I watched for a few minutes as the players—men and women in their early thirties, like me at the time—rolled dice and then looked up and made succinct, discrete movements with their miniatures. And I, knowing nothing of the rules, was reminded of how as a boy I played with action figures with my friends and my sister and myself: moving them in relation to one another, having them fight, putting them through the movements of an adventure that was, sure, primarily internal but which found material expression in toys. That’s play. And playing is what gaming has always been about.

Miniatures are where it all begins, historically. Gameplay rules for military miniatures have existed for more than two hundred years, but the seepage away from military and aristocratic patronage into the public sphere is a modern phenomenon. HG Wells wrote a set of such rules in 1913 entitled Little Wars; this text, and the invention of plastic, helped boost the popularity of complex military strategy games designed for miniature models. The trend accelerated over the course of the twentieth century (with no lack of real-world analogs on which to base the modules) and seems to have culminated in the sixties and seventies, when gaming took a distinct turn toward the mind realm.

It is by the marriage of Sword and Sorcery fantasy and military strategy games, like the intersection of a cosmic plane with a conscious being, that Dungeons & Dragons is conceived.

Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson were seasoned miniature wargamers. They each authored several rule sets for tactical strategy games, and each helped to push gameplay further into fantasy. Arneson’s Blackmoor and Gygax’s Chainmail, the precursors to Dungeons & Dragons, were medieval miniature war games with fantasy supplements.

In order to publish D&D, Gary Gygax founded Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. with his friend and fellow gamer, Don Kaye. It was 1973. In 1975, Don died unexpectedly. And the tale of the next ten years is a deeply scrutinizable saga—worthy of modules and novel series in its own right—but basically the game was hot and the company was expanding and restructuring and exploding the boundaries of the gaming franchise into the realm of the multimedia multiverse.

In 1984, Tracy Hickman and Margaret Weis delivered the first of the Dragonlance Chronicles, and with it came a massive imaginary setting (and a huge retail environment of modules and miniatures and other gaming paraphernalia). During this decade, TSR bought whole worlds from private persons—dungeon masters, let’s say—who had spent a decade or more running complex campaigns with dedicated gamers, layering detail over detail in the service of a good game. The most important of these is Ed Greenwood, from whom TSR bought the Forgotten Realms, one of the most complex imaginary worlds ever created, and a default setting for D&D modules to this day.

The 1997 acquisition of TSR and the entire Dungeons & Dragons franchise by Wizards of the Coast doesn’t so much spoil the saga (though I’m sure the haters are numerous and justified) as it does demonstrate the metamorphic, borderless nature of the whole fantasy role-play project. Before buying D&D for twenty-five million dollars, Wizards famously introduced Magic the Gathering, and later they purveyed the Pokémon trading cards. Members of their staff no doubt dabbled in D&D. These are some hardcore nerds, and also some hardcore commercial vendors. The game is and always will be in the hands of those kinds of people.

And now here we are, well into the twenty-first century, on a pile of discarded retail objects: dice, cards, boards, miniatures, books. And the internet holds in its loose grip all the accumulated wisdom of the thousands of dungeons masters who came before us. Anyone can pick up the pieces and start playing, more or less for free. All that is required is study and imagination (practices which are, in this context, barely distinguishable). In a sense, we are back to where we began: the boundless and unconstrained mind realm. (Even if Hasbro owns the whole thing by now.)

9. Day Three: Three Seventeens and a Gargoyle

During our third session, the band pushed northward up a steep incline, fighting off wolves and one worg along the way, to the magma-blackened cone of the volcano from which issued intimidating bellows and screeches of diabolic delight. Despite the dramatic setting shift, student attendance was spotty. Two players had to leave early, one came late and played only for the last ten minutes, and at least one character needed babysitting. It felt like it might be the last sesh—like maybe we’d come far enough: gotten a taste of adventure, a feel for the dice and their fatal probabilities, and had our fair bite of the vicarious nostalgia this Dungeons & Dragons cultural reboot had to offer.

But in the final ten minutes they made the dramatic decision to approach first one and then another of a sextet of grotesque statues that circled the rim of the volcano—and the second of these was a gargoyle, by far the most formidable monster they’d faced. And this extended the game six or seven minutes past our typical stop-time, and it drove the energy through the roof, and I cranked up my shitty desk speakers so that Burzum’s “Towards Ragnarok” rang all around us, and they managed a miraculous three seventeens in a row. And the gargoyle, finally vanquished, cracked and then crumbled, revealing dozens of gold coins like a living heart within the smoking wreckage, wreathed in the red light of the not-so-distant volcano blast.

10. Dice

I didn’t think the students could defeat the gargoyle—at least not with the wooden clubs I’d granted them at the start of our informal seshes. But they rolled three seventeens in a row, which struck me as very rare indeed but was in fact a pure function of randomness, lumpy and absurd. How, after seeing that, can anyone help but feel that fate is a game of chance one might cheat, either through luck or through superstition?

Dungeons & Dragons is all about storytelling, sure. That’s been the allure for me my whole life. But the real thrill—the aspect of gameplay that keeps them coming back, week after week—is dice. Players, in combat or at task completion, need to roll against an armor class (AC) or a difficulty class (DC) representing the odds of success. So essentially we are gambling: practicing the black art of probability, that oldest game. Sword and Sorcery is a fine vehicle for this drug because, at its heart, gameplay is existential speculation.

Again, I am anchored to fiction: Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, which reads like a Sword and Sorcery novel set in the mid-nineteenth-century American borderlands, is haunted by one of modern literature’s most sinister villains. Bald, enormous, perversely cruel and preternaturally powerful, Judge Holden rides like a necromantic sorcerer at the head of a band of mercenary Indian killers, occasionally holding forth on topics of war and fate and the mystical supremacy of chance.

In one memorable campfire sermon, he invokes the parable of two men who sit to play cards “with nothing to wager save their lives.” It is the ultimate game—the essential condition of existence. All human will and purpose and skill depend on the caprice of a single, simple “turn of the card. The whole universe for such a player has labored clanking to this moment which will tell if he is to die at that man’s hand or that man at his. What more certain validation of a man’s worth could there be?”

Something of this philosophy lies at the heart of the compulsive gambler. And increasingly, our sciences have come to embrace probability as a fundamental condition of matter and energy. D&D enshrines this supremacy of chance in its reliance on dice. As player characters level up, they accrue proficiency and skill bonuses that modify their die roll and increase their probability of success; but always doom lurks in the margins, merely avoidable in some mysterious, random way that we mortals can never fully understand.

Chance defines us while we are unable to define it. From the fickle crucible of luck crawl forth characters who believe in themselves—in their ability, their consciousness, their soul—in a way the merciless, dice-throwing universe does not. Down to the sub-atomic structure, we are the result of chance.

11. Day Four: Shit Gets Real/Centaurs

I gave my players up to the centaurs. I more or less forced them to accept capture and bondage for the price of their lives. What happened was this: they wandered north and ran into trouble with some hobgoblins—trouble the dice wouldn’t allow them to get out of—and before long, boom: saved and then captured by centaurs.

Next Thursday, they will arrive at the centaurs’ citadel, where they will be separated and forced to undergo separate adventures. I realize now that I have always known where this was headed. Ever since I built the board, I’ve known of the centaurs’ citadel on the river, whose mill wheels fire the bellows of their forges where they coin metal and craft high-quality weapons and musical instruments. And for at least a week, I knew that there would need to be an adventure there: an indoor adventure, like nothing we’d yet attempted: an adventure among non-player characters, with intrigue and persuasion and human error and good old-fashioned plot.

12. Lunch with the Older Gods

I needed human guidance. So I had lunch with Sam and Gabe, both seniors, both experienced gamers. Sam and I had met in the mind realm before—when he was a sophomore, he played Tybalt to my Capulet in a local park production of Romeo and Juliet—so in a sense, we had role-played together already. Gabe, incidentally, had filmed portions of our rehearsals for a TV production class. (Again we see the subtle hand of fate at the loom.)

I was not surprised when I learned that Sam played. From our time together on set, I knew that he practiced medieval swordplay at a guild level in real life. In D&D, he prefers to play fighting characters; all his magical characters have been under-utilized as spellcasters—they had a tendency, he said, to approach combat from a weapons perspective.

Sam told me that from a purely logistical stance, there is no reason to play as anything other than a human. Humans, he said, are “ridiculously advantaged” by the 5th edition rules. They garner more racial bonuses than any other type. Regardless, he currently plays as a dragonborn warrior—an aggressively imaginative character, I thought, considering the relative novelty in the franchise of the dragonborn race (the 5th edition cautions that the dragonborn do not necessarily exist in all D&D worlds, and that while all races are prevalent in the cosmopolitan centers of the multiverse, the presence of a dragonborn hero in a rural village might provoke suspicion or outright hostility).

Sam is an admittedly ultralogical gamer. He came to D&D via military strategy games, where he said the narrative element often takes the back seat to strategy. Whole ships or battalions advance or are lost in lots, and the human interest is subordinate to the dispassionate historical context. He’s only been at fantasy role-play for a short while, and at first the elements of personal heroic narrative—concerns of class, personality, and social interaction—were perplexing.

Gabe—whom Sam calls “the most experienced and qualified D&D player around”—has practiced fantasy role-play since the elementary grades. He’s DMed many times. I asked him if he ever used modules, and he said he that while he appreciates a robust homegrown adventure, he often adapts preexisting modules into his campaigns—for expediency’s sake, if nothing else. The first time he created an adventure from scratch it was so bad that it led to the disbandment of the entire club for a while. What did he do wrong? He made “the classic rookie mistake” of creating an NPC to guide them through the adventure.

I’d never considered this. Was this is a classic rookie mistake?

Gabe explained that when player characters meet a sage old wizard or something, and he guides them through the stages of a predetermined, deeply-entrenched narrative, it stunts the creativity of the group, boxing them into a fatal path where there should be room for psychic wandering, collaborative design, group storytelling.

Nowadays, he doesn’t plan too far ahead. One session. The events of each session determine the next session’s plot. Gabe said you’ve got to let the story grow on its own. The DM needs to get out of the way—let the players choose their paths, assign a probability, and then find out if they succeed. He said the only thing he cannot tolerate in a DM is a refusal to allow a character to act on his wishes, however improbable the intended outcome. So a first-level thief wants to scale a glass wall … great. Set the DC at thirty, let him roll, apply his proficiencies, move on.

Our lunch, like every public school lunch I’ve ever eaten, was short. Twenty-five minutes is nowhere near enough time to exhaust my full inquiry. I thanked them and moved on in my pursuit. For experienced players, they were exceedingly gracious. Secretly, I’d expected to be measured, found wanting, and smote into oblivion (a decent reminder, I think, of what students feel like every day in school).

13. Day Five: Level Two, I’m Not Done

Today I brought the band of adventurers as captives to the centaurs’ citadel. I described the goblin heads mounted on the parapets and ramparts. I told of the roofless interior, of the pillars of living oak with the branches that overspread the whole complex. Of the mosaic floors, and the sounds of metallurgy behind secret doors.

And I finally understood the true value of miniatures when Terran the Destroyer and Kindar the Unbathed were made to fight a captive griffon in a pit match for the amusement of the centaur captors. As soon as they started asking questions like “Can I run in the opposite direction?” and “Can I throw this stick across the room?” and “Can I jump onto the griffon’s back and stab its head?” we started using dice—two black ones and a white one—to signify the positions of the combatants inside the pit.

The griffon was whipping their asses for a while. But a questionable centaur threw two weapons down—a katar (a canonical D&D weapon) and a brass orchid (from Samuel R. Delany’s novel Dhalgren)—and the players got to strike with the d6. And I gave them their proficiency bonuses back. And I gave them the “second wind” function they rightly deserve by 5th edition rules.

The 5th edition Players Manual urges the DM to encourage adventure by keeping DCs manageable. That’s why I let Terran the Destroyer jump onto the griffon’s back. I didn’t know if it would work, but I didn’t have to. I just set the DC at ten and let him roll. Then we put a black die on top of the white one, and he stabbed his enemy with the katar, and in a few rounds they killed it and got 250 experience points each, and they both leveled up.

It was the most complex combat of the campaign. Gameplay is shaping up. The world is larger and deeper, even if it is the same world as before.

In a few months, these students will leave this world, with or without their characters, and never come back. The world will stay with me. It will be as it always was: me and the mind realm.

Perhaps others may enter. If I continue to DM.

14. Toward a Growth Mindset

The Growth Mindset model—popularized by Carol Dweck, but descended from all kinds of educational studies and theories—has been the fetish of much professional development in the past few years. To summarize, it posits that students—and people in general—are more successful and happy when they view challenges and even failures as opportunities for skill development. One is urged to shun negative thinking and language (“I can’t” becomes “I can’t yet”) and to view effort as the essential key to success.

Of all the reams of Powerpoint handouts and photocopied book excerpts that have fluttered my way in the wake of this fad, I find Bernard Weiner’s Attribution Theory the most intriguing. In a thick but cheaply bound codex intended to make me a better teacher, I found a four-square diagram, like an arcane chart of the bodily humors: each square represented one of the factors of our success or failure. These neat quadrants were split by axes dividing the internal from the external, and the fixed from the variable. The spaces were labeled: Ability, Task Difficulty, Luck, and Effort.

The implication of this chart—which is fatal and tragic, but liberating—is that three out of the four factors of our success and failure—ability, task difficulty, and luck—are entirely out of our hands. We cannot control our genetic predispositions, and our psychological and emotional states are ungovernable. The difficulty of any task is similarly fixed, but entirely external. As for weather, random interference, and other external factors of luck: forget it. Our only control mechanism is our effort.

We are at a three-to-one disadvantage to fate; but in that disadvantage, we are free. Free to submit to the whims of fate. Free to roll dice. Free to try our asses off and fail anyway and reject guilt (at least exclusive personal guilt) for the outcomes of our probabilistic adventures.

Like everything else, this corresponds directly to Dungeons & Dragons. Our characters’ abilities are derived from the dice. We have no choice but to accept their limitations and relative disadvantages. Task difficulty is set by the DM, not the players. Sure, they can parlay and bargain with their all-too-human DM, but as Gary Gygax reminds us in the official Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Masters Guide: “it is your right to control the dice at any time and to roll dice for the players.”

And luck is a function of the dice. You might hold some modifiers in your quiver—you might even have advantage—but the dice do not play favorites. They are perfect and random: a variable and external factor.

So we students are left with effort. The power of will—that same force that created the mind realm.

Our homework is to get some dice, read some books, plunge into the forest and kick some ass.

_________________

-Spring 2017